The Evolutionary Underpinnings of Mangione's "Heroism"

Thoughts on Why Some Responded Viscerally to Luigi Mangione's Alleged Actions

In the hours following the killing of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, and the release of the first surveillance video showing the shooter gunning Thompson down, public response immediately took on a form that some—particularly those in the ruling class or wealthy individuals without much anxiety regarding health care costs and coverage—didn’t expect: approval, admiration, and even affection and desire. When the surveillance shots from the hostel were released, we learned that “assassin-bae” had a smile that was a “deadly weapon.”

As most readers will remember, this phenomenon caused much pearl-clutching in the media. The BBC worried about a “dark fandom,” referring to admiration of the shooter (the suspect had not yet been identified) as “fetishization.” In that article, Professor Tanya Horeck from Anglia Ruskin University, was quoted as saying, “The mood around Luigi Mangione is ‘thirst.’”

I actually agree with Horeck. There was a lot of thirst. But the thirst I’m talking about is not the thirst she’s talking about.

The thirst I’ve seen since the events of December 4th is not sexual in nature, at least not primarily sexual (more on that later). The thirst I see is instead the visceral reaction many experienced in direct response to the killing of a health insurance CEO and to the individual accused of the crime. The thirst I see is for the establishment of a social sanction for threats to the group’s survival and, at a basic level, a thirst for recognition that there is a threat at all.

First, an author’s note: I am not an evolutionary biologist or psychologist. I’m an ex-journalist and writer, and while I did graduate with an anthropology double-major and am a lifelong “student” of these disciplines I am nowhere close to an expert in the fields of evolutionary theory, evolutionary sociology, and other related fields. These are merely my observations (although I strive for them to be informed and sourced observations).

However, I believe an evolutionary perspective on the phenomenon described above may provide an interesting counterpoint to the widely propagated take that the so-called “festishization” of Luigi Mangione and/or the shooter is a sign of social decay or a coarsening of social dialogue.

The Danger of Non-Reciprocators to the Group

With those animals which were benefited by living in close association, the individuals which took the greatest pleasure in society would best escape various dangers, while those that cared least for their comrades, and lived solitary, would perish in greater numbers. —Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

This epigraph appears at the beginning of a 2008 paper written by Mark Van Vugt and Mark Schaller, published in the journal Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. “Evolutionary Approaches to Group Dynamics: an Introduction” offers an accessible primer on group dynamics seen through the lens of evolutionary theory. In it we learn what I would consider is now mainstream information: that group living is an evolutionary adaptation, or adaptive strategy, that promotes survival and reproduction.

At the same time, we have also evolved psychological strategies or mechanisms that “have profound implications for many different aspects of group dynamics.” Part and parcel of this is the fact that group living is not and cannot be egalitarian. In other words, the benefits of group living will not be equally distributed.

Germane to our discussion about the CEO shooting is this interesting tidbit:

Among ancestral humans, fitness may have depended crucially upon the sharing of valued resources, such as food; but this created the problem of finding trustworthy partners to share food with. Because it was potentially lethal to share with people unlikely to reciprocate, natural selection processes may have favored psychological mechanisms that facilitate the identification, avoidance, and ostracism of nonreciprocators (emphasis mine). There is growing evidence that humans indeed have specialized decision rules for cheater detection and social exclusion (Kerr & Levine, 2007; Kurzban & Leary, 2001).

I’m particularly struck by this line: “it was potentially lethal to share with people unlikely to reciprocate.” When considering our collective “group” it’s not difficult to identify a class of individuals who do not reciprocate with the rest of us. Members of that class include Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Peter Thiel, Andrew Witty, and other unimaginably wealthy and powerful individuals.

They take from the group by hoarding wealth, taking advantage of government subsidies they do not need, resisting unionizing efforts aimed at fair wages and safe working conditions, interfering in democratic processes to further their own interests.

And they fail at the most basic of reciprocative behaviors in our modern society: they do not pay their fair share of taxes. Sometimes they do not pay taxes at all. Taxes, of course, are the means by which we keep our common infrastructure safe, pay for universal services like mail delivery, libraries, schools, airports—the list goes on and I don’t need to educate you on why taxes are necessary in our society. Particularly in a society with such massive income inequality.

This is all true of most corporations, as well, including United Healthcare, because corporations are also members of our “group,” having been granted personhood by our Supreme Court. Despite mining our citizenship and our government for labor and cash, these corporate persons also do very little to reciprocate for all the resources they utilize and hoard. (Incidentally, the “freeloader paradox” is well worth reading about using the lens of the current state of corporate capitalism and corporate welfare.)

From an evolutionary perspective, these individuals are a danger to the collective well-being of the group. I am arguing here that on some level, many of us understand this, whether we are able to verbalize it or not. Some of us understand this based merely on observation of how these individuals/corporations interact with the group; others have to experience the negative impacts of their lack of reciprocation firsthand, as with, for example, an unjustified claims denial from a health insurance company that has successfully used tax loopholes to avoid paying taxes.

The danger of non-reciprocators under the guise of both corporations and individuals is self-evident, but broadly, due to their resource-hoarding, the rest of the group is left with fewer resources and find themselves having to continually defend the scant resources left over from these non-reciprocators are well.

Freeloader Freddies: The Old Rules Don’t Apply

What does this have to do with “assassin-bae”? A lot, actually. Remember earlier, where I cited Van Vugt and Schaller saying that over tens of thousands of years of evolution and group living, humans have developed certain psychological mechanisms to deal with certain social dynamics?

So, part of that is the emotions we feel in response to those dynamics. We were puny, half-naked apes on an open savannah for a long time, so we certainly developed fear. We learned quickly that we had a better shot of survival if we banded together and developed a deep need for social connection and a fear of banishment (banishment meant certain death for thousands of years). Love and affection deepens social bonds, and the deeper they run, the safer we are. These sorts of emotions became part of our biology because they provided great evolutionary benefits. They helped keep us safe.

What about things that posed a threat to the group—behaviors that harmed the group's chances of survival? What about the one guy who raided the stores of food in the middle of the night because he got the munchies and then the rest of the group had to go hungry for days? Or the guy who always took just a little more than his fair share at dinner, leading to smaller portions for the children? The one who used up all the medicinal herbs for a headache instead of saving some for the critically ill mother and her children?

These individuals were removed from the group, just like any other threat would be. The term is social exclusion, and it is an adaptive mechanism that protected our early social groups from harm. Another way to put it is to say that groups optimized their chances of survival, or their fitness, by determining who should be included in the group. Those who share resources—reciprocators—would be at the top of the list. Those who hoard them would pose a danger and therefore would be excluded from the group.

Now, typically, dealing with “social parasites1” or free-riders would not require a lot of work—social sanctions, punishments, or ostracism/shame was usually enough to get people back in line.

Fast forward to right now, and those mechanisms have proven largely useless. Yes, they work on the individual level—the stick-up man, the shoplifter, the small-time fraudster, the lone murderer, all end up in jail, banished from society for a period of time.

However, social murder—a term coined by Engels to describe death caused by capitalists and capitalistic systems—goes unpunished. There are no social sanctions stopping Brian Thompson and Andrew Witty from utilizing automated claims denial software to deny people lifesaving healthcare or to play games with prior authorization in order to run out the clock on cancer patients. No punishment. And ostracism and shame have zero effect on the corporations and the individuals who not only don’t reciprocate in society but who actively harm it.

In short, many Americans feel, and with good reason, that there is no mechanism to protect the group’s well-being from these “social parasites” (the term used by Luigi Mangione in the document law enforcement alleges he wrote). The group is left unprotected from these threats, its well-being has been diminished, and the free-riders gain more and more power despite being fed only by the common resource pool, including the group’s labor.

This creates a profound emotional response, though in modern society it may feel diffuse and opaque. A general sense of discontent, frustration, and anger with no real target. There are so many free-riding corporations and individuals, all of whom seem to have incomprehensible amounts of money, and yet they want more, and they want to take it from you, someone who has scant few resources. Because of the evolutionary history in your DNA, you long for a correction to this imbalance, because you know, somewhere in your bones, that this is about survival.

And yet, there is no recourse—not for you, and not for the group. The freeloaders are going to suck the group dry. The group will not survive because the norms are not being enforced nor are the usual social sanctions.

A Group Protector Steps Forward

So, I argue that we feel this threat on a deep, visceral level, even if we don’t articulate it in terms of evolutionary biology or psychology. For those of us who are not billionaires or the wealthy butlers to the billionaire and ruling class, this fear manifests as a low-level, low-grade anxiety that is always there. We’ll occasionally lash out at a claims adjuster or a mortgage broker or a loans administrator, and we’ll rage-post, sometimes even about the freeloaders, even though we know it accomplishes nothing in the way of eliminating the threat to group survival.

But mostly we just go along, hoping for the best, worried mostly about our own survival (and our family’s), unable to find the bandwidth to worry about the well-being of the group as a whole. At least not for long periods of time.

And then someone comes along—a member of the group—and delivers a social sanction to a representative of the parasitical class and something happens to the group. Something remarkable.

Despite the rigidity of social norms, most of which have been engraved into our very beings since we were children, many of us are unable to abide by them because of a much stronger emotional response we feel but may not fully understand. Conditioned to respond to murder with horror and fear, we experience neither emotion. Instead, many of us watch and rewatch the film of the gunman who shot Brian Thompson on the streets of Manhattan in order to make sense not just of what we don’t feel, but also of what we do.

For some of us, that emotion is gratitude. Now let me be careful here, for I do not mean that these same Americans felt gratitude that the alleged gunman murdered a man in broad daylight. That is not what I mean at all. The gratitude is for the acknowledgment of the wrong perpetuated by the company and the industry the victim represented and it is gratitude for the reestablishment, however flawed and fleeting, of social sanctions that meaningfully protect the group’s well-being, even if, as in this case, that sanction is merely symbolic.

That feeling is big because it has been pent up for years. Not only that, it has been growing and growing. As Mangione is alleged to have written in the notebook law enforcement says he was found with, the insurance industry “checks all the boxes.” In other words, millions upon millions of Americans have been damaged, hurt, or even killed because of health insurance industry practices that are rewarded by our government (lack of regulation) and our capitalistic system (UHC made $22.4 billion in profit in 2024—at this time, a health insurer making a profit can only happen via harm to the group.)

Because the feeling many Americans experience upon learning of the events on December 4th, 2024 is big and intense and confusing, it goes a little sideways. Especially when it becomes clear that the gunman was competent, intentional, young, and, we later learn, traditionally handsome.

For some, the gratitude for the threat-protection became hero-worship. Hours after news broke that the bullet casings had Delay, Defend, Depose etched into them, and, as a result, it became clear that this was, as hoped by many, an ad hoc social sanction for wrongs perpetuated against the group, graffiti began appearing around the world that were homages to the shooter.

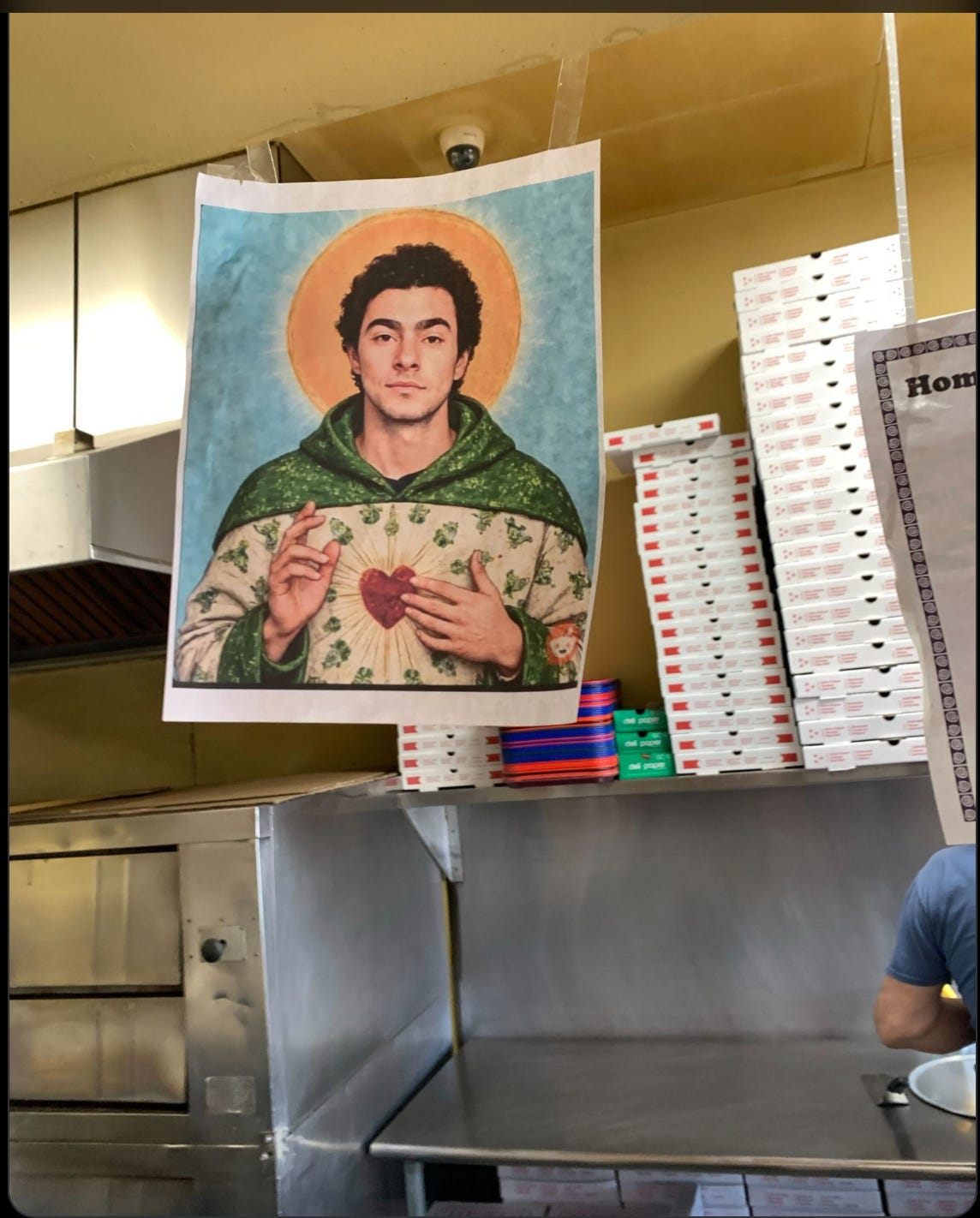

As soon as Luigi Mangione was identified as a suspect, posters featuring his face began turning up in cities across the country. He was often depicted as a saint. One of the most salient images of this hero-worship was a portrait of Mangione as “Saint Luigi” hanging in a pizza shop in Mangione’s hometown of Towson, Maryland.

Let’s sit with this saint-ification of an alleged killer for a moment. Setting aside the usual social policing rhetoric from the ruling class in whose interest it is to keep the working class docile through social norms and niceties, consider the depth of feeling required for even tongue-in-cheek deification to come into play in a scenario like this.

Another compelling bit of evidence that the killing of Brian Thompson was seen as a social sanction among a substantial portion of the population is the ecumenical nature of the approval. While this has diminished a little bit under the relentless partisan efforts to pit “leftists” and “right-wingers” against each other (something that profit-seeking influencers and talking heads do every day), in early days, there was remarkable resistance to these efforts.

“I’m MAGA-oriented and I still love what this guy did,” said one Reddit commenter. When right-wing provocateur Ben Shapiro immediately tried to pin “celebrations” of Thompson’s killing on “leftists,” he experienced so much pushback from his own right-wing fans that it made news in the mainstream press. In a country deeply fractured politically for at least ten years, the murder of a healthcare executive by a citizen created two weeks of unity—and this is indisputable. Even the NYPD’s report on public reaction to the murder indicates that approval on social media came from both left-wing and right-wing sources.

Though the ruling class, the wealthy, and their media mouthpieces scrambled to find a framing for this event that would eliminate the public’s sympathy for the suspected gunman, they failed. They didn’t know why they failed, as they’ve been wildly successful before in framing news events and political issues in a way meant to divide.

They failed because this act resonated on a deep, and I’d argue evolutionary, level with millions of Americans who have long sought to see the “group” protected from a dangerous threat. Again, even if that act of protection was symbolic. The need was so deep, and so strong, that it overrode, and continues to override, the deeply ingrained social norm that would normally shame anyone who refuses to condemn a murder.

Assassin-Bae as Norm Enforcer

Finally, on top of hero-worship, we also saw what, on the face of it, is a mildly amusing sexualization of the alleged shooter. I think it’s important to point out that even before Luigi Mangione was identified and his face hit the news, many people online had professed to have already fallen in love with the alleged shooter, based solely on the grainy video depicting the murder. When photos of the alleged shooter at a hostel emerged, which provide a look at his face, and it was widely agreed that the face was handsome, the sexualization took off, in the form of jokes, artwork, and other user-created content.

While this response was condemned by mainstream media, usually with a sexist undertone, I don’t believe it trivialized the events of December 4th. Instead, I think what Professor Horeck, from the beginning of this piece, called “thirst” was actually that gratitude for the shooter’s perceived norm-enforcing action. And it was expressed as admiration for an individual who, in evolutionary terms, demonstrated “fitness.” That is, an individual who saw the threat to the group’s survival (again, speaking in evolutionary terms) and who, in the absence of any kind of norms-enforcement, took altruistic action to protect the group.

Of course, in any group—human or non-human—the individual exhibiting the most “fitness” is the most desirable. The media can lambaste the women (and many men) who drooled over Luigi Mangione’s shirtless picture from Hawaii (now that is a thirst trap!), but the response is akin to the response gamers have to big-breasted, big-hipped female game characters or, to evoke a different epoch, the curvy, busty Playboy models of old. In the case of women, “fitness” is seen in hips broad enough for birthing and breasts healthy enough to nurse offspring. In other words, that appreciation—that sexualization—is a remnant of our evolutionary past because those traits were, once upon a time, shorthand for reproductive success.

I’d argue that seeing the alleged CEO shooter provoked a similar sexual response in many individuals. Just as a woman with broad hips was seen as a reliable choice for producing healthy offspring, a man willing to thwart threats for the good of the group (and his family), was seen as an ideal choice for a mate. In our complex, modern society, with the seemingly infinite layers of “civilization” laid atop our deeply ingrained evolutionary biology and psychology, Luigi Mangione became, to some, the ideal man.

In this case, does it help that Mangione was young, physically fit, and handsome? Of course, just as it would’ve if the alleged shooter had been an attractive female. But, and this is important, this conclusion could only exist if the group members felt they were under threat.

I think this post on Instagram Threads by a user named raxb16 three days after the shooting and three days into the manhunt for the shooter captures what I’m trying to say here:

Gentlemen,Reasons Assassin Bae is hot that are not his jawline: 1)he made a plan and executed it 2)he has values that do not flow with the stock market 3)he has made a stance against financial ‘prima nocta’ (refusing to let them force themselves on me? Mother may I 😜) 4) seriously I cannot stress number one enough.Hope this helps 😘

Why the Public Response, then, Is the Least Surprising Thing Ever

No matter how complex our society becomes, no matter how fractured our politics, how cynical the populace, how massive the wealth gap, the underpinnings of our communal life are rooted in tens of thousands of years of group living, specifically cooperative living. We’ve entered an age where the non-reciprocators in our group have ascended to immensely powerful positions, while still hoarding resources and stealing labor from other group members. Non-reciprocators may have private jets, rocket ships, $600 million weddings, and influence over our government, but they remain members of the group. Our group. They are us.

We cannot understand the events of December 4th and, far more important, in my opinion, the public response to those events, without understanding our long history as social creatures who depended upon one another for survival. With unmitigated threats to our survival from our own non-reciprocating group members, and no social sanctions to deal with those threats, there should be absolutely no surprise that group members appreciate one of their own who took it upon himself to be a norms-enforcer.

Just a footnote here to acknowledge the fraught, problematic history of the term “social parasites.” As I will mention later, it has been used predominantly to describe poor people, those who utilize social welfare programs, etc.. If this term can’t be eliminated from our vocabulary, I’d love to see it applied to those who actually do have a parasitic relationship to the group, namely corporations and billionaires.

This is the analysis I’ve been hunting for. An answer to the craving feeling of all this. Thank you.

Great piece, enjoyed reading it. Perhaps we should re-evaluate whether the evolutionary story we tell ourselves is correct, or continues to be relevant. In my opinion, Antigone is another story we need to frame this, I'll write it up... In the meantime, I am reminded of Elie Wiesel's lesson in _Night_, that it wasn't the good, kind, and generous who survived - they were among the first to die in the Nazi death camps. When you become wealthy, life comes to be all about keeping that wealth. You become fearful, of loosing it and of others, and you separate yourself, as much as your wealth permits, from others socially and spatially. In my assessment, the very wealthy quite literally live in another reality, one that is designed to shield them from any and all social consequences of their resource hoarding. This is why Luigi's alleged actions are so lauded. If it was him, he used his male and social-economic privilege, and his intelligence, to make a mark, and that is almost unheard of. Martin Luther King Jr. reminded us those in power do not willingly give it up... I speculate that something happened inside Luigi's family, that his family's wealth and situation was not used to protect him and his health. Maybe his parents wanted him to grow up and applied some tough love, after L went off to Japan instead of adulting.... Anyhow, a few crazy philosophers (Wittgenstein, Marx I think?) have voluntarily given up their wealth and lived according to principle, but I don't know of many others. Anyone know any other such stories, of people acting on principle and against what is their socio-political or class interests?